One of the main tools of climate scientists is simulations. These powerful computer programs are used to see what the climate will do in the future based on current inputs. But the important thing to know about these simulations is that they are “past tested.” They take the world as it was a long time ago, run the program, and if it works right they should get the results of recorded history. If we have more climate records, and more accurate climate records we can make better and better programs to tell the future. Those who forget the past, are condemned to repeat it.

The Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) drillship JOIDES Resolution is returning to port in Honolulu this week after a two-month voyage to chart detailed climate history in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. The expedition was the first of two back-to-back voyages of a scientific project called Pacific Equatorial Age Transect (PEAT). It was the first international scientific drilling expedition after the JOIDES Resolution underwent a multi-year transformation into a 21st-century floating science laboratory.

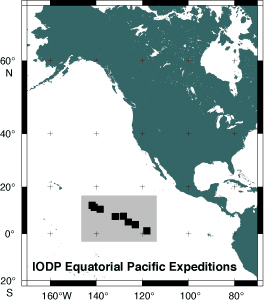

The PEAT expeditions are recovering a series of continuous historical records in sediments at a number of different geographic locations beneath the equatorial Pacific Ocean. The first research effort, called Expedition 320, took place March 5 through May 4, 2009; Expedition 321 will take place from May 5 through July 5, 2009.

Co-chief scientists of Expedition 320 were Heiko Palike of the University of Southampton, U.K., and Hiroshi Nishi of Hokkaido University in Japan. On Expedition 320, scientists obtained records from the present back in time to the warmest sustained “greenhouse” period on Earth, which took place around 53 million years ago.

Shipboard studies have revealed that changes in ocean acidification linked to climate change have a large and global impact on marine organisms.

“The sediments collected during this expedition offer an unprecedented window to the evolution of the tropical Pacific, one of the largest and most climatically important ocean regions on Earth,” said Julie Morris, director of NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences.

“In focusing on a time period that includes some of the best analogs for abrupt climate change, extreme climate events, ocean acidification, and ‘greenhouse’ worlds, the results will give us insights into the potential impacts of future climate change.”

Environmental changes are recorded by shells of tiny microfossils that make up the deep-sea sediments.

“We can use the microfossils and layers of this sediment ‘archive’ as a yardstick for measuring geologic time,” said Expedition 320 co-chief scientist Hiroshi Nishi.

“This will allow us to determine the rates of environmental change, such as the rapid first expansion of large ice-sheets in the Antarctic 33.8 million years ago. This polar process had a profound impact on phytoplankton even at the equator.

“We managed to retrieve several records of this important climate transition.”

Expedition 320 co-chief scientist Heiko Pälike said that “it’s truly remarkable to see 53 million years of Earth’s history pulled up onto the drillship’s deck, then pass through our hands, and move past our eyes. We saw first-hand the effects of Earth’s climate machine in action.”