The bulk of the world’s fisheries–including the kind of small-scale, often non-industrialized fisheries that millions of people depend on for food–could be sustained using community-based co-management. This is the conclusion of a study reported in this week’s issue of the journal Nature.

“The majority of the world’s fisheries are not–and never will be–managed by strong centralized governments with top-down rules and the means to enforce them,” says Nicolas Gutiérrez, a University of Washington fisheries scientist and lead author of the Nature paper.

“Our findings show that many community-based co-managed fisheries around the world are well managed under limited central government structure, provided communities of fishers are proactively engaged,” he says.

“Community-based co-management is the only realistic solution for the majority of the world’s fisheries, and is an effective way to sustain aquatic resources and the livelihoods of communities depending on them.”

Under such a management system, responsibility for resources is shared between the government and users.

“This important research shows that a better understanding of ecological, social and economic interactions–and shared responsibilities for management–can yield sustainable well-being for ecosystems and fishers alike,” says Phillip Taylor, section head in the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research.

On the smallest scale, this might involve mayors and fishers from different villages agreeing to avoid fishing in each other’s waters.

Examples on a larger scale include protecting Chile’s most valuable fishery. In 1988, local fishers in a single community began cooperating along a 2-mile (4-kilometer) stretch of coastline. Today it involves 700 co-managed areas with 20,000 artisanal fishers along 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) of coastline.

“It’s encouraging to see new models for sustainable fisheries management being proposed, especially those that incorporate the human dimension as a key component in solutions,” says David Garrison, director of the NSF’s Biological Oceanography Program.

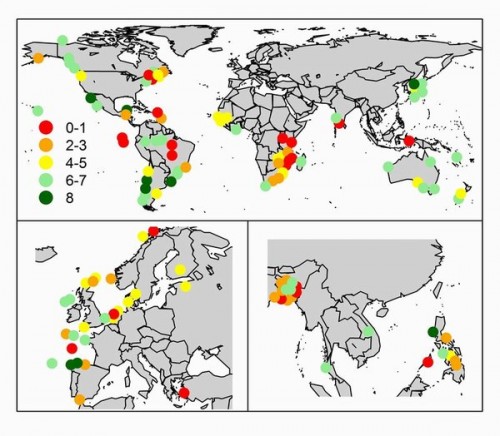

While case studies of individual co-managed fisheries exist, this new work used data on 130 fisheries in 44 developed and developing nations, and included marine and freshwater ecosystems as well as diverse fishing gears and targeted species.

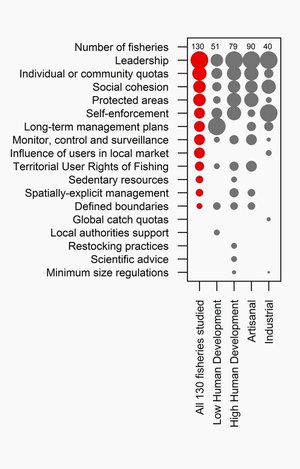

Statistical analysis shows that co-management typically fails without: prominent community leadership and social cohesion clear incentives that, for example, give fishers security over the amount they can catch or the area in which they can fish and protected areas, especially when combined with regulated harvest inside or outside the area and when the protected area is proposed and monitored by local communities.

“Additional resources should be spent on efforts to identify community leaders and build social capital rather than only imposing management tactics without user involvement,” says Gutiérrez.

The study further confirms the theories of Elinor Ostrom, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for challenging the conventional wisdom that common property is always poorly managed, and should be either regulated by central authorities or privatized.

Resource users frequently develop sophisticated mechanisms for decision-making and rule enforcement, Ostrom said, to handle conflicts of interest.

“With community-based co-management, fishers are capable of self-organizing, maintaining their resources and achieving sustainable fisheries,” says Omar Defeo, a biologist at the University of Uruguay, scientific coordinator of Uruguay’s national fishery management program, and a co-author of the paper.

Gutiérrez and colleagues assembled data from scientific literature, government and non-government reports, and personal interviews for 130 co-managed fisheries.

They scored them on eight outcomes–ranging from community empowerment, to sustainable catches, to increases in abundance of fish and prices of what was caught.

With 40 percent of the fisheries scoring positively on 6, 7 or all 8 outcomes, and another 25 percent scoring positively on 4 or 5 of the outcomes, the scientists found that community-based co-management holds promise for successful and sustainable fisheries worldwide.

Ray Hilborn, a University of Washington fisheries biologist and a co-author of the paper, says that these findings “further illustrate the world’s growing ability to manage fisheries sustainably.

“The tools appropriate for industrial fisheries in countries with strong central governments are quite different from those in small-scale fisheries or countries without strong central governments.”

The work was also supported by the Fulbright-Organization of American States Ecology Program, and the Pew Charitable Trusts.