In a strange and odd bit of happenstance right around the time I was done with college I was slated to go join an AmeriCorps program in Louisiana. The whole point of this program was to revitalize the delta region so that sediment from the Mississippi river would help create a buffer against things like hurricanes. George W. Bush de-funded that program so I ended up in Texas instead. Several years later Katrina struck New Orleans and we saw the folly of ignoring problems like this. Now with things like global warming, and the threat of continued storms many have asked what we are going to do to protect the famous city.

Diverting sediment-rich water from the Mississippi River below New Orleans could generate new land in the river’s delta in the next century. The land would equal almost half the acreage otherwise expected to disappear during that period, a new study shows. For decades, sea-level rise, land subsidence, and a decrease in river sediment have caused vast swaths of the Mississippi Delta to vanish into the sea.

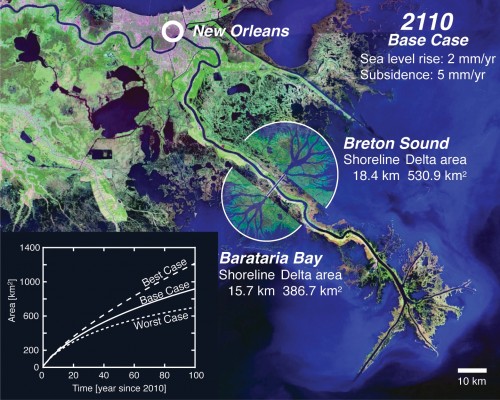

The anticipated build-up of new land in a portion of the delta, as simulated by a computer model, could compensate for a large fraction of the expected future loss, protect upriver areas from storm surges, and create fresh-water habitat, the researchers say.

“What this model shows is that we can, to a large degree, match future land loss by making these diversions,” says David Mohrig, a geologist at the University of Texas (UT)-Austin who is also affiliated with the National Science Foundation (NSF)’s National Center for Earth-surface Dynamics at the University of Minnesota.

He and Wonsuck Kim, also a geologist at UT-Austin, led the study. Its results are reported in today’s issue of Eos, the weekly newspaper of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

“These authors present the possibility that through numerical modeling, coordinated with river channel diversions on the Mississippi Delta, we can begin to restore wetlands and build new land,” says H. Richard Lane, program director in NSF’s division of earth sciences, which funded the research.

The delta of the Mississippi River has been losing land to the sea at an average rate of about 44 square kilometers (17 square miles) per year since around 1940.

The natural equilibrium between soil loss and sediment deposition has been altered by the levees the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built below New Orleans to prevent the Mississippi from flooding.

The confined waters at the end of the river’s course flow faster and drop their sediments over the continental platform, draining into the Gulf of Mexico.

History recorded in the river deposits shows that the main channel of the Mississippi moved roughly every 1,000 years to a new lowland area, Kim and Mohrig say. The engineering of the levees, they believe, has kept the river from entering lowland areas and depositing sedimentation.

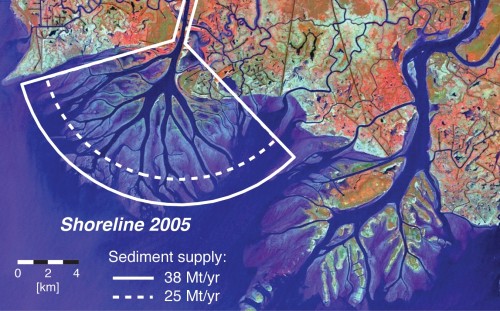

The model looks at potential effects of an existing proposal to divert Mississippi River water through a pair of cuts made opposite each other in the levees 150 kilometers (93 miles) downstream from New Orleans.

Nearly half of the river’s flow would spill out through the cuts, taking sediment with it and depositing it to each side of the river channel.

Despite sea level rise, increased land sinking rates, and a drop in the river’s sediment supply, the diversions would create an amount of new land equal to up to 45 percent of the area that would otherwise be lost to the sea in the coming century, the model predicts.

Enough flow would remain in the main channel of the river to allow navigation there, the researchers report.

Other scientists studying coastal restoration had previously proposed creating these two diversions to allow water and sediment to exit the enclosed river, and build two lobes of new land in adjacent shallow-water sections of Breton Sound and Barataria Bay.

But critics say that dams in the upper sections of the Mississippi River have reduced the water’s sediment content so much that there isn’t enough raw material left to rebuild the delta. Also, detractors argue that future sea level rise and the current high sinking rate of the delta would make restoration impossible.

“Until we put together this model, there was a lot of debate that wasn’t substantiated by anything but by intuition,” says Mohrig. “We needed to move from having very soft impressions of what could be done to making predictions that can actually be tested.”

The modelers used a conservative sediment supply rate, subsidence (sinking) rates from one to 10 millimeters per year, and rates of sea level rise that went from zero to four millimeters per year.

In their calculations, the authors considered diverting only 45 percent of the water to ensure that the section of the river below the diversions remained open to navigation.

The model predicts that the two diversions would create between 701 square kilometers (about 271 square miles) and 1,217 square kilometers (470 square miles) of new land over a century, partially offsetting land loss.

Kim and Mohrig calculate the engineered new delta lobes would make up for 25 to 45 percent of the area expected to vanish throughout the delta between now and 2110.

“Diversions are really the only cost-effective way of building land,” Mohrig says.

The researchers verified their model by running a simulation of the evolution of another delta influenced by an existing diversion of the Mississippi River: the Old River Control Structures.

These structures divert water from the Mississippi to the Atchafalaya River, which also empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atchafalaya River is currently building new land both in the Atchafalaya Delta and its subsidiary, the Wax Lake Delta. The model was able to accurately predict the amount of land that has been built since 1980.

Mohrig and Kim collaborated on the model with scientists from Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge; the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; and the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.