Some amoebae do what many people do. Before they travel, they pack a lunch.

In results of a study reported today in the journal Nature, evolutionary biologists Joan Strassmann and David Queller of Rice University show that long-studied social amoebae Dictyostellum discoideum (commonly known as slime molds) increase their odds of survival through a rudimentary form of agriculture.

Research by lead author Debra Brock, a graduate student at Rice, found that some amoebae sequester their food–particular strains of bacteria–for later use.

“We now know that primitively social slime molds have genetic variation in their ability to farm beneficial bacteria as a food source,” says George Gilchrist, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Division of Environmental Biology, which funded the research. “But the catch is that with the benefits of a portable food source, comes the cost of harboring harmful bacteria.”

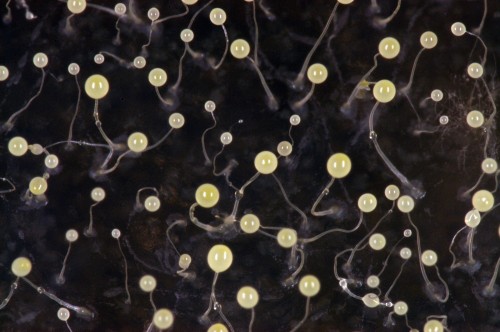

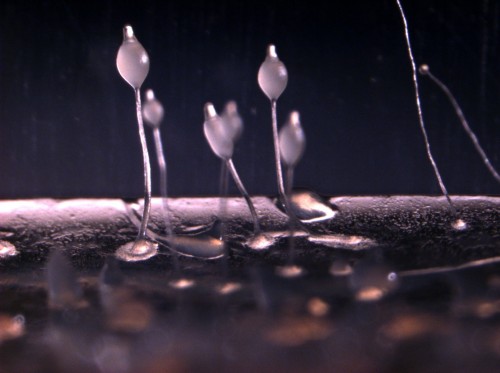

After these “farmer” amoebae aggregate into a slug, they migrate in search of nourishment–and form a fruiting body, or a stalk of dead amoebae topped by a sorus, a structure containing fertile spores. Then they release the bacteria-containing spores to the environment as feedstock for continued growth.

The findings run counter to the presumption that all “Dicty” eat everything in sight before they enter the social spore-forming stage.

Non-farmer amoebae do eat everything, but farmers were found to leave food uneaten, and their slugs don’t travel as far.

Perhaps because they don’t have to.

The advantages of going hungry now to ensure a good food supply later are clear, as farmers are able to thrive in environments in which non-farmers find little food.

The researchers found that about a third of wild-collected Dicty are farmers.

Instead of consuming all the bacteria they encounter, these amoebae eat less and incorporate bacteria into their migratory systems.

Brock showed that carrying bacteria is a genetic trait by eliminating all living bacteria from four farmers and four non-farmers–the control group–by treating them with antibiotics.

All amoebae were grown on dead bacteria; tests confirmed that they were free of live bacteria.

When the eight clones were then fed live bacteria, the farmers all regained their abilities to seed bacteria colonies, while the non-farmers did not.

Dicty farmers are always farmers; non-farmers never learn.

Rice graduate student Tracy Douglas co-authored the paper with Brock, Queller and Strassmann. She confirmed that farmers and non-farmers belong to the same species and do not form a distinct evolved group.

Still, mysteries remain.

The researchers want to know what genetic differences separate farmers from non-farmers. They also wonder why farmer clones don’t migrate as far as their counterparts.

It might be a consequence of bacterial interference, they say, or an evolved response, since farmers carry the seeds of their own food supply and don’t need to go as far.

Also, some seemingly useless or even harmful bacteria are not consumed as food, but may serve an as-yet-undetermined function, Brock says.

That has implications for treating disease as it may, for instance, provide clues to the way tuberculosis bacteria invade cells, says Strassmann, infecting the host while resisting attempts to break them down.

The results demonstrate the importance of working in natural environments with wild organisms whose complex ties to their living environment have not been broken.