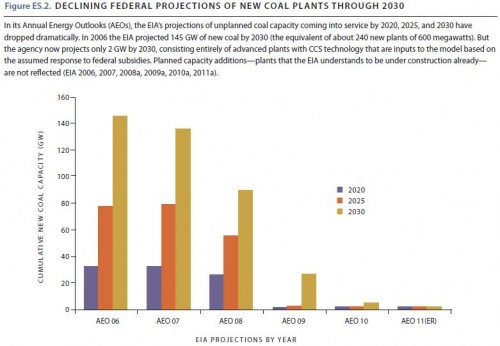

The cost of constructing or retrofitting coal-fired electric power plants and the rising cost of coal have made coal power an extremely risky long-term investment, according to a report released today by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS). The report, “A Risky Proposition: The Financial Hazards of New Investments in Coal Plants,” also identified a number of other factors that make investing in coal a gamble, including its continuing threat to public health and the environment.

“We have a fleet of ancient, dirty coal plants in this country that are increasingly unreliable and long past due for retirement,” said Barbara Freese, a co-author of the report and senior policy analyst for the UCS Climate and Energy Program. “Plant owners have to decide whether to sink more money into retrofitting those old plants or replacing them with much cleaner energy technologies. But even if they retrofit them with the pollution controls available today, the plants will still emit massive amounts of carbon pollution.

“Replacing old, dirty coal plants with cleaner, cheaper, less risky alternatives would be a much better bet,” she added. “And it would save lives, protect our health and reduce the emissions that cause climate change.”

More than 70 percent of U.S. coal-plant-capacity is already more than 30 years old—the operating lifetime for which coal plants were typically designed—and a third went online before 1970. Some plant operators have announced they will retire old plants. Others are planning to retrofit their plants with modern pollution control technology—which would reduce emissions of several dangerous pollutants, but not carbon.

Such investments would not only make it harder to protect the climate, the report concluded, but also expose investors and ratepayers to a host of financial threats.

The factors that make coal power such a precarious investment include:

- U.S. coal prices are rising and could be driven much higher by soaring global demand, especially from Asia. Spot prices for Appalachia coal spiked dramatically in 2008, largely due to international demand, and those prices are steadily rising again with the global economic recovery. And the price for a one-month contract for coal from Wyoming’s Powder River Basin rose 67 percent between October, 2009 and October, 2010. While western coal has been less exposed to volatile global markets, that situation appears to be changing since major coal producers in the West have announced plans to increase their exports to China and other Asian markets.

- Coal prices could also be driven higher by constraints on supply. The amount of economically-recoverable coal reserves may be smaller than previously thought.

- Major coal projects face high, unpredictable construction costs. The cost of building a new coal plant in the United States has roughly doubled in the past five years.

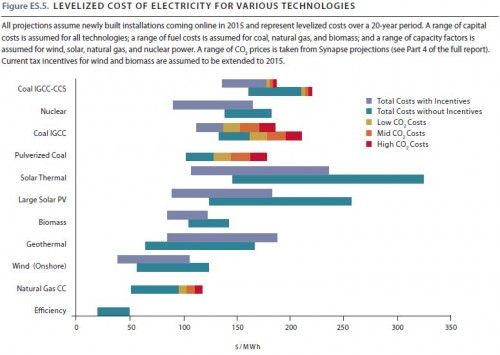

- The cost advantage coal power traditionally enjoyed over cleaner energy options has largely disappeared when it comes to new plants. Power from new coal plants now costs more than power from new gas plants, wind facilities and the best geothermal sites, and much more than investing in energy efficiency.

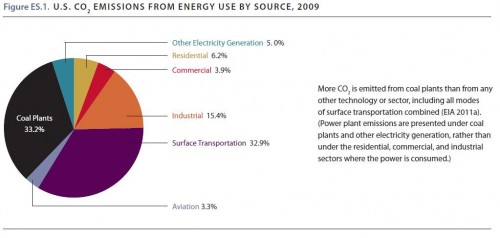

- Coal power is the largest U.S. carbon pollution source—contributing about one-third of all energy-related emissions and more than the entire surface transportation sector. Coal-fired power plants inevitably will face increasing pressure to dramatically cut emissions to help curb climate change. The cost of generating electricity from new coal plants could increase 11 to 37 percent under a range of carbon prices in the future.

- Carbon-capture and storage (CCS) retrofits cannot be counted on to affordably cut emissions. Federal studies show that adding CCS to a new plant could increase the cost of generating electricity 36 to 78 percent, while retrofitting an existing plant could increase its costs by 330 percent.

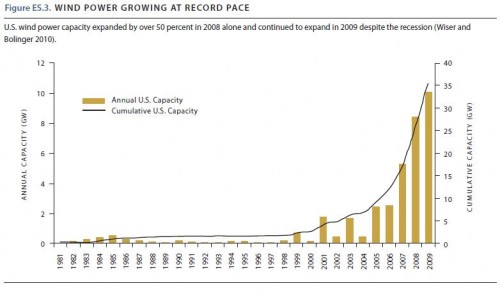

- Federal and state governments are promoting energy efficiency and clean energy sources, which will cut demand for coal power. Twenty-seven states have energy efficiency standards or a standard pending, and several states now require annual reductions in electricity use of at least 2 percent. Twenty-nine states now have a standard requiring utilities to increase their reliance on renewable energy sources, more than doubling since 2004.

- Coal plants also face new costs associated with such harmful emissions as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide, which are associated with thousands of deaths annually, and mercury, which threatens the brain development of infants and children.

The owners of the most damaging older coal plants have been taking advantage of a legal loophole for decades, Freese pointed out. Clean air legislation and rules put in place in the 1970s did not require existing plants to install pollution control equipment until their next major modification. It was assumed that they would either modify or shut down within a few years.

“But coal operators kept these plants running well beyond their expected retirement dates and never installed the pollution controls newer plants were required to use,” Freese said.

Even with this loophole, federal air regulations have gone a long way to protect the public health.

The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, for example, signed into law by George Herbert Walker Bush, prevented as many as 160,000 premature deaths last year alone, according to the

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The amendments also were cost effective. According to the EPA, they’ve cost $65 billion to implement, but their overall financial benefit could reach $2 trillion by 2020.

“The success of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments shows that requiring coal plants to cut their pollution leads to public health and economic benefits many times higher than the cost for old coal plants to comply with the law,” Freese said. “The amendments have done a lot of good, but we need to do more. Coal plants are still linked to the deaths of thousands of Americans yearly and many other health threats.”

Finally, according to the report, the electric power industry could retire many old coal-fired plants without causing reliability problems with the power grid, Freese said.

“First, there is a lot of extra generating capacity on the grid right now. And second, energy efficiency and renewable energy investments are reducing the need for coal. It’s a good time to retire coal plants.”