We told you about some bad ass microbes that were making a life for themselves at the bottom of the ocean in horrific conditions, well it would seem give life a challenging environment and more often than not it will be able to find a way to grow there.

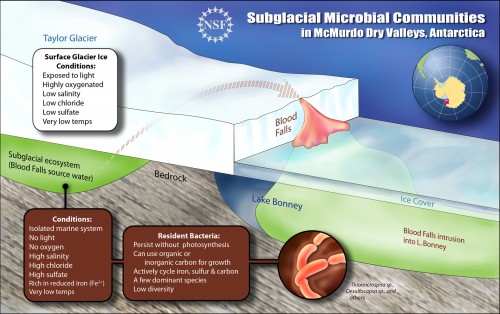

An unmapped reservoir of briny liquid chemically similar to sea water, but buried under an inland Antarctic glacier, appears to support unusual microbial life in a place where cold, darkness and lack of oxygen would previously have led scientists to believe nothing could survive, according to newly published research.

After sampling and analyzing the outflow from below the Taylor Glacier, an outlet glacier of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet in the otherwise ice-free McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica, researchers believe that, lacking enough light to make food through photosynthesis, the microbes have adapted over the past 1.5 million years to manipulate sulfur and iron compounds to survive.

The microbes also are remarkably similar in nature to species found in marine environments, leading to the conclusion that the populations under the glacier are the remnants of a larger population of microbes that once occupied a fjord or sea that received sunlight. Many of these marine lineages likely declined, while others adapted to the changing conditions when the Taylor Glacier advanced, sealing off the system under a thick ice cap.

The research will be published in the April 17 edition of the journal Science.

The research answers some questions and raises others about the persistence of life in extreme environments such as under glaciers, or even in liquid lakes trapped kilometers under the Antarctic ice sheet, environments that until recently scientists would not have believed could support living creatures.

“Among the big questions here are ‘how does an ecosystem function below glaciers?’, ‘How are they able to persist below hundreds of meters of ice and live in permanently cold and dark conditions for extended periods of time, in the case of Blood Falls, over millions of years?,” said Jill Mikucki, the lead author on the paper.

The Dry Valleys are completely devoid of animals and complex plants and scientists consider them to be one of the Earth’s most extreme deserts. The Valleys receive, on average, only 10 cm (3.93 inches) of snow each year. Despite the lack of precipitation, during the Antarctic summer, temperatures rise just enough for glaciers protruding into the valleys to begin melting. The meltwater forms streams that enter lakes covered by ice that is two to three stories thick.

Mikucki and her colleagues based their analysis on samples taken at the ominously, but aptly named Blood Falls, a water-fall-like feature at the edge of the glacier that flows irregularly, but often has a strikingly bright red appearance in stark contrast to the icy background.

The Dry Valleys have been the target of scientific inquiry since the early days of Antarctic exploration in the so-called “Heroic Age” early in the 20th Century. Even the earliest explorers noted the massive stain at the snout of the glacier and speculated as to what may have caused it.

“The original explorers,” Mikucki said, “thought that red alga was responsible for the bright color.”

More than a century later, the Dry Valleys remain a source of immense scientific curiosity. One of NSF’s Long-Term Ecological Research projects network of 26 sites worldwide is located there. And, as part of its research program during the International Polar Year (IPY), NSF supported an extended research season in the Dry Valleys, allowing scientists for the first time to stay in the field as six months of darkness descended to study how the microscopic creatures there reacted.

In the paper, however, Mikucki and her colleagues argue that the creatures that survive under the Taylor Glacier are both far more exotic and far more adaptable than the early explorers thought.

Because the outflow from the glacier follows no clear pattern, it took a number of years to obtain the samples needed to conduct an analysis. Finally she obtained a sample of an extremely salty and clear liquid for analysis.

“When I started running the chemical analysis on it, there was no oxygen,” she said. “That was this when got really interesting, it was a real ‘eureka’ moment.”

Further genetic analysis suggests that of the relatively small numbers of microorganisms found in the brine, “the majority of these organisms are from marine lineages,” she said.

In other words, microorganisms more similar to those found in an ocean than on land, but capable of surviving without the food and light sources available in the open ocean.

“The salts associated with these features are marine salts, and given the history of marine water in the dry valleys, it made sense that subglacial microbial communities might retain some of their marine heritage,” she added.

This led to the conclusion that the ancestors of the microbes beneath the Taylor Glacier probably lived in the ocean many millions of years ago. When the floor of the Valleys arose more than 1.5 million years ago, a pool of seawater from the fjord that penetrated the area was trapped. The pool was eventually capped by the flow of the glacier.

The briny pond, whatever it’s size “is a unique sort of time capsule from a period in Earth’s history,” Mikucki said. ” I don’t know of another environment quite like this on Earth.”

Life below the Taylor Glacier may help scientist address questions about life on “Snowball Earth”, the period of geological time when large ice sheets covered the Earth’s surface. But it’s also a rich laboratory for studying life in other hostile environments, including the subglacial lakes of Antarctica and perhaps even on other icy planets in the solar system such as below the Martian ice caps or in the ice-covered oceans of Europa, a moon of Jupiter.