We have talked before about how global warming can change the way that jellyfish act. A new study helps explain a cyclic increase and decrease of jellyfish populations, which transformed parts of the Bering Sea–one of the U.S.’s most productive fisheries–into veritable jellytoriums during the 1990s.

The study shows that the availability of food for jellyfish may cap the potential size of the Bering Sea’s jellyfish population, even while other factors, such as rising temperatures, may encourage its continued growth.

These results indicate that “anticipated temperature increases in the Bering Sea will not necessarily further increase its jellyfish populations,” says Lorenzo Ciannelli of Oregon State University, a co-author of the study. By contrast, in warmer latitudes, jellyfish frequently multiply as temperatures rise.

The study provides potentially good news for the Bering Sea’s fishing industry, which has been damaged by jellyfish blooms. Nicknamed “America’s fish basket,” the Bering Sea produces more than half of the U.S.’s entire catch of fish and shellfish.

Described in the May 29, 2008 online issue of Progress in Oceanography and summarized online in Nature, the study was partially funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

The Rise and Fall of Jellyfish

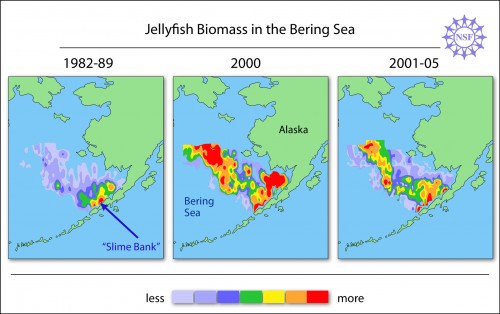

During the 1990s, the Bering Sea’s jellyfish reproduced with such wild abandon that by about 2000, they were about 40 times more abundant than they had been in 1982, according to analyses of collections from fishing trawls made in the Bering Sea by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. In addition, starting in 1991, Bering Sea jellyfish expanded their ranges by fanning out north and west of the Alaskan Peninsula.

Because of these changes, one area north of the Alaskan Peninsula–always famous for its jellyfish–became so jellified that fishermen nicknamed it “Slime Bank” and began avoiding it altogether for fear of filling their nets with jellyfish. Other fisheries were damaged as well.

The Bering Sea’s jellyfish population peaked in 2000, and then eventually stabilized at moderate levels between those of the bloom years of the 1990s and the less populated years of the 1980s. The post-2000 population decreases occurred while water temperatures dramatically increased–even though increasing temperatures have been associated with increasing jellyfish numbers in lab studies and in other waters, such as Narragansett Bay.

What is causing this apparent incongruity in the Bering Sea? “We think that once the Bering Sea’s jellyfish population outsized the available food supply, the jellyfish population probably shrunk,” says Ciannelli.

A Squishy Scourge

The most common jellyfish in the Bering Sea is the northern sea nettle, which has tentacles up to six meters long. Sea nettles and other jellyfish damage the fishing industry by: 1) gumming up fishing nets, 2) stinging captured young fish, which spoils their commercial value, and 3) consuming young fish, which may reduce the sizes of commercial catches.

Do More Blooms Loom?

“There are still too many mysteries about Bering Sea jellyfish to predict their next moves,” says Ciannelli. These mysteries include whether food for jellyfish is being increased by the fishing industry’s removal of jellyfish competitors that eat the same food that jellyfish eat.

In addition, “the Bering Sea’s current jellyfish population is still much bigger and ranges further than it did during the 1980s,” observes Ciannelli. “This finding suggests that water temperatures influence jellyfish populations. But we don’t know how and how much.”

Desparately Seeking Polyps

Scientists suspect that increasing water temperatures may influence jellyfish population in various ways. For example, they may:

* Impact the food supplies of jellyfish.

* Prolong an early developmental stage for jellyfish during which they live as tiny, bottom-dwelling polyps before developing into swarming adults. If this occurs, there may be time lags between ongoing increases in water temperatures and resulting appearances of adult jellyfish swarms.

* Cause polyp habitats to move. Such movements may be reflected in the recent expansion of jellyfish habitats.

“No one has ever seen jellyfish polyps in the Bering Sea,” says Ciannelli. “So we don’t know how temperature changes impact them.” That is why Ciannelli and colleagues are currently using new computer models to help track down probable polyp locations. “We must find those polyps,” Ciannelli affirms.

The Long Tentacles of Environmental Change

Scientists generally agree that human-caused stresses, including global warming and overfishing, are encouraging jellyfish surpluses in many tourist destinations and productive fisheries. These jellyfish-rich locations include Australia, the Gulf of Mexico, Hawaii, the Black Sea, Namibia, the United Kingdom, the Mediterranean, the Sea of Japan and the Yangtze Estuary.

Study Implications

“This study–which represents a multi-disciplinary effort between experts in marine ecology, statistics and the mathematical geosciences–does more than just answer important questions about jellyfish ecology,” says NSF Program Director Grace Yang. “It also provides a model for estimating populations based on incomplete data.” Such models may be applied to other marine and land-based ecological studies and to studies of the spread of infectious diseases, says Yang.

Because our oceans are so vital to our food resources, and the survival of every living thing on the planet you should take some time to help Greenpeace protect them…got this in the mail today.

It’s probably no surprise to you that our oceans are in trouble and desperately need our help. At Greenpeace, we’ve been campaigning all over the globe for increased marine conservation and it looks like the oceans may be getting a hand from a very unlikely source.President Bush is thinking about designating sizeable portions of U.S. territorial waters as marine protected areas. In 2006, Bush brought large-scale ocean conservation to the U.S. by establishing a Marine National Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the world’s largest fully protected marine reserve.

Maybe President Bush has a special place in his heart for the oceans? Whatever the reason, we need more marine reserves and we need to encourage President Bush to follow through and make this a reality!

Most U.S. waters remain unprotected from destructive fishing practices, so additional steps are urgently needed to help reverse the alarming decline of the health of our oceans.

We need more marine reserves because they help restore marine biodiversity and put endangered species and habitat on the road to recovery. They provide a safe haven for marine life, enabling populations to re-build and re-seed surrounding areas. Marine reserves also can help us understand the changes caused by global warming, even as the reserves help increase marine ecosystems’ ability to withstand these new climate stresses.

Please take action today.

Hi would you mind if I used and modified this Jellyfish image for my own artwork? I need a Jellyfish for a composition. Very nice shot. Would be much appreciated.

Kind Regards,

Simon