Was it just my imagination, or did I hear a small ripple of applause from the forests, the wetlands and the glaciers, as the news of the collapse of Bear Stearns leaked into the public realm? There are many precursors of economic collapse; one is the sudden upturn in the price of gold, another is a rise in the little known “skyscraper index” — both of which signal the move by the wealthy to invest their money into things that may hold their value longer than pieces of electronic data whizzing around the networks of the world’s investment banks and clearing houses. No one will be surprised that Bear Stearns’ collapse means recession is imminent, and the investors are popping Prozac like cups of coffee.

And that ripple of applause? It’s because with recession comes a drop in consumer spending, a reduction in the number of goods being made and moved around the world, a slump in the sale of houses, vacations, big cars, air conditioning, patio heaters: a downturn in the carbon engine that has, for the last three decades been driving the global temperature inexorably upwards as the amount of money swilling around in the consumer economy keeps growing.

Recession stops greenhouse gases being emitted.

This is no piece of environmental wishful thinking. While researching A Matter Of Scale, I discovered that the link between global trade and carbon emissions was closer than I had ever suspected.

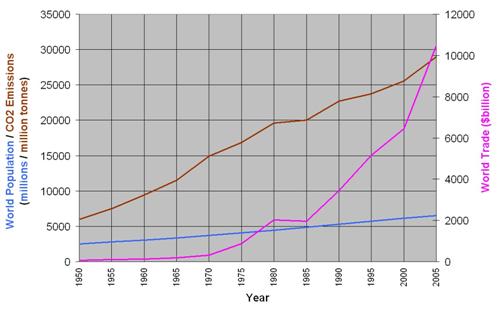

Between 1950 and 1970, international trade (imports and exports) grew from $60 billion to a still relatively modest $317 billion: growth of 413 percent in 20 years is impressive, but nothing compared to later on. International trade started to climb rapidly after 1975 – because the graph only shows trade between different nations, the freeing up of international markets during the 1970s is particularly visible, as is the massive global recession in the 1980s, and the explosive growth in the international trade of consumer goods since 2000.

These variations in world trade between 1975 and the present day are closely matched by changes in carbon dioxide emissions – with the notable exception of the early-1990s, when the smokestacks of much of Europe stopped belching with the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, and the emergence of natural gas as a cleaner generator of electricity. This blip was not to last long.

Recessions may hurt the indebted individual; some of whom have hardly enough to feed their family, but many more who have over-reached with their desire to buy things on credit that they would otherwise have done without – was that new TV or car really necessary? More than that, though, global recessions hurt the capitalist drug-pushers who keep topping up our desire to keep the global economic engine growing with their cries of, “Buy! Buy! Buy!”.

As they now cry, “Sell! Sell! Sell!” how many of them will start to realise that the price tag on the atmosphere is far bigger than any mortgage, far bigger than any pension, and a great deal bigger than the global economy.