Satellite imagery from the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder reveals that a 13,680 square kilometer (5,282 square mile) ice shelf has begun to collapse because of rapid climate change in a fast-warming region of Antarctica.

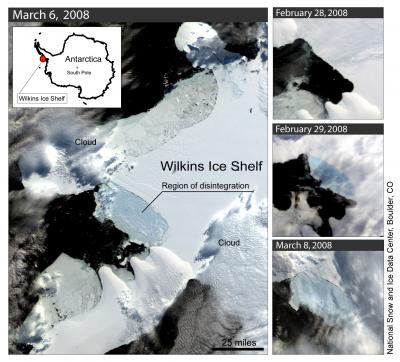

Figure 1. This series of satellite images shows the Wilkins Ice Shelf as it began to break up. The large image is from March 6; the images at right, from top to bottom, are from February 28, February 29, and March 8. NSIDC processed these images from the NASA Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) sensor, which flies on NASA's Earth Observing System Aqua and Terra satellites.

The Wilkins Ice Shelf is a broad plate of permanent floating ice on the southwest Antarctic Peninsula, about 1,000 miles south of South America. In the past 50 years, the western Antarctic Peninsula has experienced the biggest temperature increase on Earth, rising by 0.5 degree Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) per decade. NSIDC Lead Scientist Ted Scambos, who first spotted the disintegration in March, said, “We believe the Wilkins has been in place for at least a few hundred years. But warm air and exposure to ocean waves are causing a break-up.”

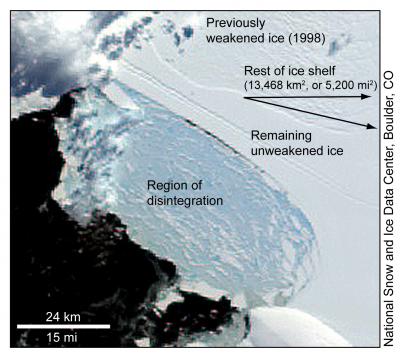

Satellite images indicate that the Wilkins began its collapse on February 28; data revealed that a large iceberg, 41 by 2.5 kilometers (25.5 by 1.5 miles), fell away from the ice shelf’s southwestern front, triggering a runaway disintegration of 405 square kilometers (160 square miles) of the shelf interior (Figure 1). The edge of the shelf crumbled into the sky-blue pattern of exposed deep glacial ice that has become characteristic of climate-induced ice shelf break-ups such as the Larsen B in 2002. A narrow beam of intact ice, just 6 kilometers wide (3.7 miles) was protecting the remaining shelf from further breakup as of March 23 (Figure 2).

Scientists track ice shelves and study collapses carefully because some of them hold back glaciers, which if unleashed, can accelerate and raise sea level. Scambos said, “The Wilkins disintegration won’t raise sea level because it already floats in the ocean, and few glaciers flow into it. However, the collapse underscores that the Wilkins region has experienced an intense melt season. Regional sea ice has all but vanished, leaving the ice shelf exposed to the action of waves.”

Figure 2. During the break-up, the Wilkins Ice Shelf broke into a sky-blue pattern of exposed deep glacial ice. This true-color image of the Wilkins Ice Shelf was taken by MODIS on March 6, 2008.

With Antarctica’s summer melt season drawing to a close, scientists do not expect the Wilkins to further disintegrate in the next several months. “This unusual show is over for this season,” Scambos said. “But come January, we’ll be watching to see if the Wilkins continues to fall apart.”

Real-time collaboration images from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and data from ICESat showed that the ice shelf was in a state of collapse in March. Scambos then alerted colleagues around the world, seeking to ensure that every means of gathering information was focused on the break-up.

British Antarctic Survey (BAS) mounted an overflight of the crumbling shelf, collecting video footage and other observations. BAS glaciologist David Vaughan said of the ice shelf, which is supported by a single strip of ice strung between two islands, “Wilkins is the largest ice shelf on West Antarctica yet to be threatened. This shelf is hanging by a thread.”

Figure 3. This image shows a high-resolution, enhanced-color image of the Wilkins Ice Shelf in Antarctica on March 8, 2008. Narrow iceberg blocks (150 meters wide, or 492 feet) crumbled into house-sized rubble. Taiwan's Formosat-2 satellite acquired this image.

The combined efforts of these international teams have begun to provide observational data that will improve scientific understanding of the mechanisms behind ice shelf collapse. Scambos said, “The Wilkins is an example of an event we don’t see very often. But it’s a key process in being able to predict how sea level will change in the future.”

The Wilkins is one of a string of ice shelves that have collapsed in the West Antarctic Peninsula in the past thirty years. The Larsen B became the most well-known of these, disappearing in just over thirty days in 2002. The Prince Gustav Channel, Larsen Inlet, Larsen A, Wordie, Muller, and the Jones Ice Shelf collapses also underscore the unprecedented warming in this region of Antarctica.

This is pretty scary stuff. While this wont raise sea level, it is a canary in the coal mine. This giant sheet of ice is big, but there are much larger ones, and they are warming at a rapid pace. I await with morbid curiosity to see how bad things will have to get before we start to take serious action.