Forests in the United States and other northern mid- and upper-latitude regions are playing a smaller role in offsetting global warming than previously thought, according to a study appearing in this week’s issue of Science.

The study, which sheds light on the so-called missing carbon sink, concludes that intact tropical forests are removing an unexpectedly high proportion of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thereby partially offsetting carbon entering the air through industrial emissions and deforestation.

The Science paper was written by a team of scientists led by Britton Stephens of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colo. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

“This research fills in another piece of the complex puzzle on how the Earth system functions,” said Cliff Jacobs of NSF’s Division of Atmospheric Sciences. “These findings will be viewed as a milestone in discoveries about our planet’s ‘metabolism.'”

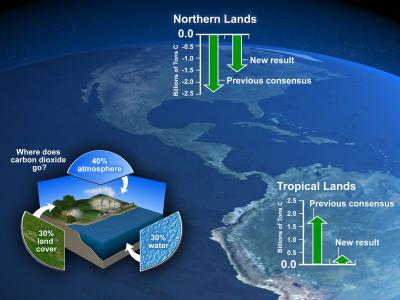

Stephens and his colleagues analyzed air samples that had been collected by aircraft across the globe for decades but never before synthesized to study the global carbon cycle. The team found that some 40 percent of the carbon dioxide assumed to be absorbed by northern forests is instead being taken up in the tropics.

“Our study will provide researchers with a much better understanding of how trees and other plants respond to industrial emissions of carbon dioxide, which is a critical problem in global warming,” Stephens says. “This will help us better predict climate change and identify possible strategies for mitigating it.”

For years, one of the biggest mysteries in climate science has been the question of what ultimately happens to the carbon emitted by motor vehicles, factories, deforestation and other sources.

Of the approximately 8 billion tons of carbon emitted each year, about 40 percent accumulates in the atmosphere and about 30 percent is absorbed by the oceans. Scientists believe that terrestrial ecosystems, especially trees, are taking up the remainder.

Computer models that combine worldwide wind patterns and measurements of carbon dioxide taken just above ground level indicate that northern forests are taking up about 2.4 billion tons. However, ground-based studies have tracked only about half that amount, leaving scientists to speculate about a “missing carbon sink” in the north.

To test whether the computer models were correct, Stephens and his collaborators turned to flasks of air that had been collected by research aircraft over various points of the globe.

The air samples had been collected and analyzed by seven labs, where they were used to investigate various aspects of the carbon cycle, but this is the first time scientists used them to obtain a picture of sources and sinks of carbon on a global level.

The research team compared the air samples to estimates of airborne carbon dioxide concentrations generated by the computer models. They found that the models significantly underestimated the airborne concentrations of carbon dioxide in northern latitudes, especially in the summertime when plants take in more carbon.

The aircraft samples show that northern forests take up only 1.5 billion tons of carbon a year, which is almost 1 billion tons less than the estimate produced by the computer models.

The scientists also found that intact tropical ecosystems are a more important carbon sink than previously thought. The models had generally indicated that tropical ecosystems were a net source of 1.8 billion tons of carbon, largely because trees and other plants release carbon into the atmosphere as a result of widespread logging, burning and other forms of clearing land.

The new research indicates, instead, that tropical ecosystems are the net source of only about 100 million tons, even though tropical deforestation is occurring rapidly.

“Our results indicate that intact tropical forests are taking up a large amount of carbon,” Stephens explains. “They are helping to offset industrial carbon emissions and the atmospheric impacts of clearing land more than we realized.”

Most of the computers models produced incorrect estimates because, in relying on ground-level measurements, they had failed to accurately simulate the movement of carbon dioxide vertically in the atmosphere.

The computer models tended to move too much carbon dioxide down toward ground level in the summer, when growing trees and other plants take in the gas, and not enough carbon dioxide up from ground level in the winter.

As a result, scientists believed that there was less carbon in the air above mid-latitude and upper-latitude forests, presumably because trees and other plants were absorbing high amounts.

Conversely, scientists had assumed a large amount of carbon was coming out of the tropics and moving through the atmosphere to be taken up in other regions. The new analysis of aircraft samples shows that this is not the case.

“With this new information from aircraft samples we see that the models were overestimating the amount of uptake in the north and underestimating uptake in the tropics,” says Kevin Gurney of Purdue University, a co-author of the paper and coordinator of the TransCom study. “To figure out exactly what is happening, we need improved models and more atmospheric observations.”

The research team comprised scientists from Colorado State University, Purdue University, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in the United States; as well as from the Laboratory of Climate Science and the Environment (France), Tohoku University, National Institute for Environmental Studies, and Nagoya University (Japan), Central Aerological Observatory and Sukachev Institute of Forest (Russia), University of Leeds (United Kingdom), Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry (Germany), and CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research (Australia).

These new findings make the preservation of existing tropical forests ever more important. While plating trees in mid and northern latitudes will help, it is the tropical rain forests that seem to absorb the most carbon dioxide. Functioning as the lungs of the world the remaining tropical forests may be critical to our survival as a species.

It’s the Sun. Mars, Jupiter, Titan and Pluto are heating up too. Wow, what an arrogant population we are!